Each spring waterfowl biologists across North America fly over breeding grounds to estimate breeding populations of waterfowl and habitat conditions. Duck seasons are determined primarily on the basis of the population status of breeding mallards and the attendant habitat conditions for breeding ducks. Historically, waterfowl regulations were set on a continental basis, with allowance made for the relative numbers of hunters and waterfowl abundance in each of the four Flyways. The U. S. Fish and Wildlife Services Regulations Committee meets in late summer to establish federal frameworks for hunting regulations for migratory birds the next fall. These frameworks establish the maximum number of days in the hunting season and maximum allowable bag limits.

States then establish their regulations so they fall within the federal frameworks. That is, states may be more conservative (for example shorter season) than the federal frameworks but they cannot be more liberal. In the 1990s, the USFWS began to move toward model based decision making processes. Adaptive harvest management was first developed for continental mallard populations.

This approach compared predictions from four different population models with observed changes in mallard breeding populations, Each year, models that better fit the data receive higher weights, meaning they have more influence on the next year’s regulations.

Regulations are set so that they achieve three goals. First, they maximize long term mallard harvest, under the assumption that the current models and their assigned weights currently reflect mallard population dynamics. Second they attempt to maintain mallard populations nearer the continental goal by reducing harvest when populations are below the goal.

The Pacific Flyway has always enjoyed the longest season and most liberal waterfowl bag limits because hunter numbers are lower and waterfowl more abundant in this Flyway when compared to the others. However, basing waterfowl regulations on continental duck counts didn’t make sense to a lot of folks; why should the numbers of mallards in the Atlantic Flyway influence the hunting season in the Pacific Flyway was a question that was often asked. To account for regional differences in waterfowl abundance and wetland habitat conditions the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service began to work with the Flyways in the early 1990’s to refine the way in which harvest regulations were determined and base regulations in each Flyway more on the status and expected breeding success for those areas that supply the vast majority of their harvested ducks.

These efforts culminated in the Pacific Flyway Council recommending to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service that a western mallard adaptive harvest management model be implemented for the 2008-2009 hunting season. The U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service adopted the Western Mallard strategy proposed by the Pacific Flyway Council in June, 2008 and used this strategy to determine the 2008-2009 season frameworks for the general duck season in the Pacific Flyway.

This Western Mallard Model gives waterfowl biologist and managers within the Pacific Flyway a better system for making sound management recommendations based specifically on those stocks of ducks that they actually harvest. Here in the Pacific Flyway the majority of harvested mallards come from breeding grounds in Alaska (approximately 800,000 in recent years), western Canada (about 400,000), and the western coastal states (about 400,000). Duck hunters in Nevada and throughout the Pacific Flyway are less vulnerable to the boom and bust cycles of the traditional prairie breeding grounds due to the western mallard’s different breeding area and ability to maintain steadier breeding populations.

This Western Mallard Model gives waterfowl biologist and managers within the Pacific Flyway a better system for making sound management recommendations based specifically on those stocks of ducks that they actually harvest. Here in the Pacific Flyway the majority of harvested mallards come from breeding grounds in Alaska (approximately 800,000 in recent years), western Canada (about 400,000), and the western coastal states (about 400,000). Duck hunters in Nevada and throughout the Pacific Flyway are less vulnerable to the boom and bust cycles of the traditional prairie breeding grounds due to the western mallard’s different breeding area and ability to maintain steadier breeding populations.

Managers believe that adoption of a specific western mallard model will result in more stability for duck seasons over the long term because Western Mallard populations tend to be more stable than those associated with the prairie regions of the continent, where wetland go through periodic boom and bust cycles.

Managers believe that adoption of a specific western mallard model will result in more stability for duck seasons over the long term because Western Mallard populations tend to be more stable than those associated with the prairie regions of the continent, where wetland go through periodic boom and bust cycles.

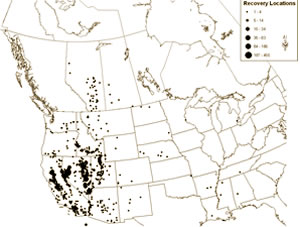

Biologists from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Canadian Wildlife Service, New York Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit, and the University of Nevada Reno have all been involved in trying to understand population dynamics of mallards that breed within the Pacific Flyway so appropriate parameters could be developed for a Flyway specific western mallard adaptive harvest management model. The first thing biologist did was spatially delineate and separate the stock of western mallards from mallards in the remainder of the continent using banding, harvest and breeding population data (Fig. 1). They concluded that mallards breeding in Alaska, Yukon, British Columbia, and the coastal Pacific Flyway states formed the western mallard stock. Presently only estimates of breeding mallards located in Alaska, Oregon, and California are used to directly influence regulations in the Pacific Flyway. Population information from other areas in the range of Western mallards is not used at this time because long-term population data was not available or the surveys that are conducted currently utilize different protocols that made their addition a case of “apples and oranges” so that biologists could not interpret the total population trends. Presently efforts are underway to add additional areas (i.e. Washington,

British Columbia, Utah, and Nevada) to those States presently surveyed. A serious issue for the future is maintaining adequate funding to sustain existing survey programs and add additional areas that are not presently surveyed.

British Columbia, Utah, and Nevada) to those States presently surveyed. A serious issue for the future is maintaining adequate funding to sustain existing survey programs and add additional areas that are not presently surveyed.

After delineation of western mallards was completed, biologists began the complicated process of building a mathematical model that would predict the allowable harvest from a number of attributes of the Western Mallard Population that could be measured each year. These attributes include measures of survival rate (what percent live through a given year), mortality (harvest and naturally occurring deaths), reproduction (the relative number of young produced per each adult female), population size and other aspects thought to influence future population status. Once a model was constructed that mimicked the historic data fairly closely biologists used the model to test a variety of harvest rates (the percentage of the population harvested) that ranged from high to low to determine what optimal harvest rates would be. The current result of this approach suggests to biologists that the harvest rate of mallards under the existing liberal season and current population trends in the Pacific Flyway is less than what could be allowed and still ensure that the long-term conservation of the Western Mallard Population.

Currently, biologists believe that as long as the western mallard stock is above 500-600 thousand mallards, then the optimal choice for long-term conservation is the current liberal season used in the Pacific Flyway. This outlook could change, however, as Pacific flyway harvest of mid-continent mallards is incorporated into models. Pacific Flyway hunters currently harvest some mallards assigned to the mid-continent stock and Pacific Flyway regulations could be altered to meet management objectives for these mallards.

The process of developing this model and implementing it for the Pacific Flyway and its hunters has taken a considerable amount of time and effort by many different people and agencies, including the U.S. Fish and Wildlife, Nevada Department of Wildlife, Nevada Waterfowl Association and the rest of the Pacific Flyway agencies. Some of those involved are your local Nevada Department of Wildlife and Nevada Waterfowl Association staff as well as faculty from UNR. These folks have nothing but the best intentions for you and these natural resources we all love and enjoy.

Dan Collins is currently a Wildlife Biologist and Assistant Pacific Flyway Representative with U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Division of Migratory Game Bird Management based out of Portland Oregon. He is also in the process of completing his Ph.D. in wildlife management from Stephen F. Austin State University in Nacogdoches, Texas. Dan studied the effects management practices had on aquatic invertebrates, seed bank potential, seed yield, decomposition rates, change of vegetation over time, food item selection, feather molt, and body condition of 3 dabbling duck species (i.e., blue-winged teal, green-winged teal, and Northern shoveler).

By Dan Collins, USFWS